History of Transylvania

Read below some excerpts from the memo sent to King Carol II by the political leaders of Transylvania almost 80 years ago. Two remarks:

1. The power of history to repeat itself is absolutely terrible!

2. The evil is contagious: nowadays, the Balkanisms referred to in the Memorandum are part of everyday life, and when it is only about the native Transylvanians and the native Banatans…

Sire,

( … ) The Constitution of 1923 was imposed on Transylvania and Banat, as on the whole country, in an abusive manner, without its consent.

( … ) Governments totally devoid of prestige and popularity in these provinces threw their political clientele on Transylvania and Banat.

With illegal methods, they have imposed as parliamentarians unknown persons, often notorious traitors of the national cause during the foreign yoke, and have filled the political and administrative functions with elements foreign to the local circumstances and the citizens of these lands. They dismissed from service well known Ardelenians and Bãnãțeni, enjoying a good reputation, connoisseurs of the needs and spirit of the province. Elements with great merits in the past national struggles for the unity of our state were drowned in the ironic smiles of satisfaction of the minorities.The methods of unscrupulous exploitation, a headlong rush for the enrichment of the satellites, turned by immorality and defiant corruption, have hurt the public sentiment of the province, once morally healthy to the point of austerity.

The centralist system did not understand what has always been for the Romanians an elementary principle of political wisdom: the method of gradual assimilation, without violent procedures, of the new provinces, by respecting their traditions, conceptions and customs, by decentralizing public services and by attracting representative and valuable local elements to an active collaboration in public and administrative life.

These methods of political wisdom were trampled underfoot in the face of a province that had not been conquered, but had united by an act of free and enthusiastic consent. The process of assimilation should have been done gradually and cautiously, not only to spare entrenched sensibilities, customs and institutions, but also so as not to pluck the flowers with the weeds, and not to destroy the good and healthy traditions with the removal of the state organization and foreign influences.(And while everything was being done to exclude the Transylvanian element from the helm of public affairs, when the riches of Transylvania and Banat were being systematically monopolized, public opinion was lamenting with wonder that, after so many years after the union, not even the beginning of a Romanian bourgeoisie had been formed in the cities across the mountains.

Instead of a new epoch of material recovery and moral upliftment, the work of humiliating the provinces and pauperizing them continued, the removal of the Romanian element from the Ardean and Banat from immoral public offices and through a favoritism which was in no way justified.

( … ) In general, the Transylvanian and Banat Romanians, instead of increasing their economic strength, find themselves in an inferior situation compared with the past. The Transylvanian barns, once the pride of this province, in full progress before the war, today are brought down to the ground. The priesthood, the intelligentsia, the wealthier part of the country have suffered billions in losses. But what is more painful is the lack of cheap credit for the peasantry, which, unable to emigrate to America, is no longer able to obtain the investment capital needed for its progress, the development and modernization of the rural economy. Of all the serious consequences of the regimes we have endured, the state of economic stagnation of the proud Transylvanian peasantry, which followed its political leaders in all the struggles of the past with great enthusiasm and ran with pure confidence to Alba-Iulia to vote for union, is the phenomenon which fills us who have been at the head of it during those struggles with deepest sorrow.

The only social class which has increased in number in Transylvania and Banat is the civil service, especially the class of the small public salaried, living on very modest salaries.

( … )Although struck in their vital interests and humiliated in their national pride and democratic conscience, Ardeal, Banat, Crișana and Maramureș not only reject with indignation and disgust the continual suspicions of alleged separatism which are hurled at them with insulting ease, but are deeply tormented by a feeling of fear, worry and uncertainty as to their future.

And they also note the paradoxical situation that, while the representatives of the minorities in Transylvania can meet freely and are almost daily watched and listened to by the rulers of the country, their demands being quickly and graciously satisfied, the representatives of the Romanian people, living in the same province, are kept aside and are not given the opportunity to show the thoughts and feelings which are more than ever troubling the country’s founding element.( … )

Your Majesties too submissive and too far gone:

Iuliu MANIU (n.n., died in the ’50s in Sighet prison), former president of the Governing Council, former president of the Council of Ministers; Dr. Mihai POPOVICI (n.n., imprisoned in the ’50s in Sighet), former minister, senator by right; Dr. Emil HAȚIEGANU (n.n., imprisoned in Sighet in the 1950s), former minister; Sever BOCU (n.n., died in Sighet prison in the 1950s), former minister; Prof. Dr. Valer MOLDOVAN (n.n., died in Sighet in the 1950s), former under-secretary of state; ( …); Dr. Ilie LAZÃR, deputy for Maramureș (n.n., imprisoned in Sighet in the 1950s) ( … )

REFLECTIONS and EXPLANATORY NOTES

( … ) What is the assessment of 20 years of the regime in Transylvania and Banat? One can say with a murmur a complete disaster. Ardeal and Banat were held for 20 years, with one brief exception, in permanent opposition. In these years of long opposition all their best forces were wasted. The liberal dictatorship has still kept up appearances. The current dictatorship has also kept up appearances. It has sent 23 active colonels from the Old Kingdom to head the 23 counties of Ardeal and Banat as Prefects. He put the military in charge of the counties. He deprived them of their soldier’s duties and gave them political posts. Ardeal and Banat were given the epithet of occupied lands. In addition to the counties, the military occupied the towns, all the towns in Transylvania and Banat. Out of 68 towns, 64 were still occupied by officers from the Old Kingdom. Following public reaction, this number was later reduced, but the system remained. ( … ) By what right was the occupation of the town halls in Transylvania? Communal estates are possessions, private property. This occupation can only be done with the right of war and not with this. The foreign men sent in this way are no longer mayors, but custodians, appointed to enemy possessions. In the meantime, more officers were replaced by civilians. And worse. They’re recruited in Bucharest at a coffee-house flea market. It’s not enough to characterize a decadence of law, to which I’ve been lunulating. It would seem like a conscious, methodical preparation for the road to Bolshevism? ( … )

From our experience, they could have known that decentralization means not only to devolve bureaucratic attributions from ministries to counties, but also the means. So decentralization does not deserve its name, it is only deconcentration, maybe not even that. ( … ) These “royal residents” are nothing more than transmitters of documents from the periphery to the center, mailboxes, located in 10 counties. No new life, no rebirth springs up in their wake, the torpor goes on, only discontent registers a new growth.

( … )We will illustrate by an example, what has been done with what was expected to be done. Let us take the example of Timiș County [established by the Administrative Law of August 14, 1939. Timiș County comprised the districts (counties) Timiș-Torontal, Arad, Caraș, Severin, and Hunedoara -n.m.], a relatively rich county. From this county, the State collects about 5-6 billion per year. Do you know how much of these billions he has left for his administrative, cultural, economic, health, etc. needs? 200 million! ( … )

The 200 million is spent almost entirely on salaries and materials. ( … ) For many years, all the international roads, both Hungarian and Yugoslav, have been turned into motorway highways, but we have none. ( … )

In the meantime, we destroyed the Romanian press in Transylvania and Banat and gave it an unsuspected flourishing minority. Sire, this foreign press has under us a real era of abundance. Before the war (1918), the strongest Romanian press was in Transylvania and Banat, not in the Kingdom. ( … )

No new roads were built, no major public institution was established, no economic or sanitary protection measures were taken. Maramures remained without a direct railroad with the rest of the country. ( … )

We are fighters, political representatives of a people, and not scarecrows or conspirators. Our struggle is an open struggle, in which we are neither intimidated nor cowed. We have neither the egos of the convictions of our doctrines, we have but one ego, the ego of the splendor of the Crown and the Nation. Despotism, autocracy and tyranny inevitably and fatally create the struggles for freedom. The severe laws enacted by Your Majesty call them something else: delinquents. Society has never seen them as criminals, but as heroes. In all peoples and in all times. Isn’t it a pity, a cry to heaven, that in these times, to polarize Romanian heroism in such a way, Romanians against Romanians, when together, and we are not yet enough, to face the dangers? ( … )

As a result of these considerations, the desire of the Transylvanian people is concretized in the respectful prayer:

Please, Sire, restore freedom to the Romanian people!

Cultural genocide refers to the systematic destruction of the culture, identity and way of life of an ethnic, national, religious or cultural group, without necessarily involving the physical extermination of members of that group. Rather than being physically eliminated, individuals are deprived of the essential elements that define their collective identity, such as language, traditions, history, history, religion, and cultural practices.

Elements of cultural genocide may include:

Suppression of language: the imposition of another official language and prohibition of the use of the mother tongue in schools, institutions, and public life.

Destruction of cultural and religious symbols: Destruction of monuments, churches, mosques, synagogues, and other important cultural and religious sites or artifacts.

Prohibition of traditions: Suppression of celebrations, rituals, customs or any practice related to the cultural identity of a group.

Indoctrination and forced assimilation: The imposition of an alternative education system that minimizes or distorts the history and culture of a group in order to force members of that group to adopt the dominant culture.

Separating children from their families: Removing children from their families to educate them in institutions that promote a different culture, separating them from their cultural heritage.

Historical examples of cultural genocide:

The policy of assimilation of indigenous peoples in North America and Australia: Indigenous children were taken away from their parents and placed in re-education schools where they were forbidden to speak their language or practice their traditions.

Sinicization of Tibet: China’s policies of integrating Tibet, which have included the suppression of the Tibetan language and Buddhist religious practices, are often considered forms of cultural genocide.

Policies of Russification in the Soviet Union: Under Stalin, ethnic minority groups were forced to give up their language and culture, promoting Russian culture and language in all aspects of public life.

Cultural genocide has no formal definition in international law similar to physical genocide, but it is recognized as a serious form of abuse against an ethnic or cultural group and is sometimes linked to processes of colonialism and imperialism.

Cultural genocide refers to the systematic destruction of the culture, identity and way of life of an ethnic, national, religious or cultural group, without necessarily involving the physical extermination of members of that group. Rather than being physically eliminated, individuals are deprived of the essential elements that define their collective identity, such as language, traditions, history, history, religion, and cultural practices.

Elements of cultural genocide may include:

Suppression of language: the imposition of another official language and prohibition of the use of the mother tongue in schools, institutions, and public life.

Destruction of cultural and religious symbols: Destruction of monuments, churches, mosques, synagogues, and other important cultural and religious sites or artifacts.

Prohibition of traditions: Suppression of celebrations, rituals, customs or any practice related to the cultural identity of a group.

Indoctrination and forced assimilation: The imposition of an alternative education system that minimizes or distorts the history and culture of a group in order to force members of that group to adopt the dominant culture.

Separating children from their families: Removing children from their families to educate them in institutions that promote a different culture, separating them from their cultural heritage.

Historical examples of cultural genocide:

The policy of assimilation of indigenous peoples in North America and Australia: Indigenous children were taken away from their parents and placed in re-education schools where they were forbidden to speak their language or practice their traditions.

Sinicization of Tibet: China’s policies of integrating Tibet, which have included the suppression of the Tibetan language and Buddhist religious practices, are often considered forms of cultural genocide.

Policies of Russification in the Soviet Union: Under Stalin, ethnic minority groups were forced to give up their language and culture, promoting Russian culture and language in all aspects of public life.

Cultural genocide has no formal definition in international law similar to physical genocide, but it is recognized as a serious form of abuse against an ethnic or cultural group and is sometimes linked to processes of colonialism and imperialism.

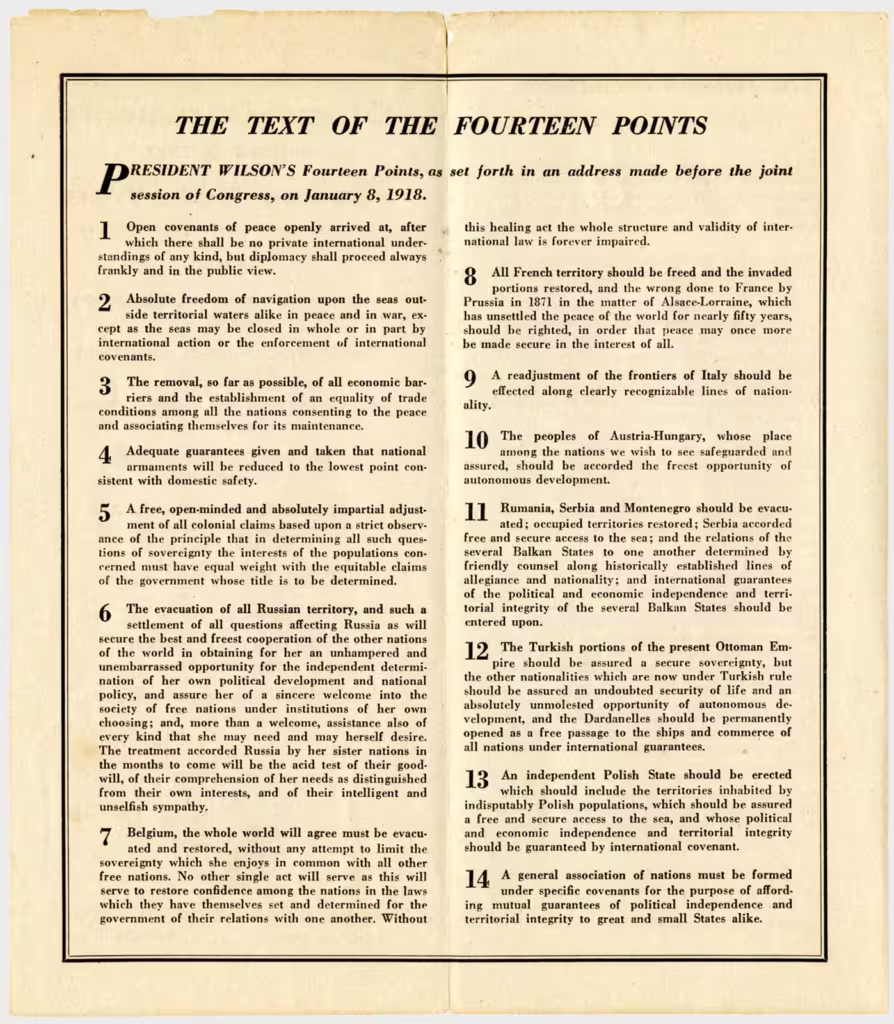

President Woodrow Wilson’s 14 points (1918) (https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/president-woodrow-wilsons-14-points)

In this speech to Congress on January 8, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson proposed a 14-point program for world peace. These points were later taken as the basis for peace negotiations at the end of World War I.

In this speech of January 8, 1918, entitled “War Aims and Peace Terms,” President Wilson laid out 14 points as a blueprint for world peace to be used for peace negotiations after World War I. The details of the speech were based on reports generated by The Inquiry, a group of about 150 political and social scientists organized by Wilson’s longtime adviser and friend Colonel Edward M House. Their task was to study Allied and American policy in almost every region of the globe and to analyze the economic, social, and political facts likely to emerge in the peace conference discussions. The team began its work in secret and eventually produced and collected nearly 2,000 separate reports and documents and at least 1,200 maps.

In his speech, Wilson directly addressed what he saw as the causes of the world war, calling for the abolition of secret treaties, the reduction of armaments, the adjustment of colonial claims in the interests of indigenous peoples and settlers, and freedom of the seas. Wilson also made proposals that would ensure world peace in the future. For example, he proposed the removal of economic barriers between nations, the promise of “self-determination” for oppressed minorities, and a world organization that would provide a system of collective security for all nations. Wilson’s 14 points were designed to undermine the will of the Central Powers to proceed and inspire the Allies to victory. The 14 points were broadcast around the world and fired from rockets and shells behind enemy lines.

When the Allied leaders met at Versailles in France to formulate the treaty ending World War I with Germany and Austro-Hungary, most of Wilson’s 14 points were overruled by the leaders of England and France. To his dismay, Wilson discovered that Britain, France and Italy were mainly interested in making up what they had lost and gaining more by punishing Germany. Germany quickly learned that Wilson’s plan for world peace did not apply to her.

However, Wilson’s climax, calling for a world organization to provide a system of collective security, was included in the Treaty of Versailles. This organization would later be known as the League of Nations. Although Wilson launched a relentless missionary campaign to overcome the US Senate’s opposition to adopting the treaty and joining the League, the treaty was never adopted by the Senate and the United States never joined the League of Nations. Wilson would later suggest that, without American participation in the League, there would have been another world war within a generation.

Transcript

It is our desire and our purpose that the peace processes, when they are commenced, shall be absolutely open and shall not henceforth involve or permit secret understandings of any kind. The day of conquest and aggrandizement is past; so is the day of secret deals made in the interests of certain governments and liable, at an unforeseen moment, to disturb the peace of the world. This happy fact, which is now clear to every public man whose thoughts do not yet linger in an age that is dead and gone, makes it possible for every nation whose aims are consistent with justice and the peace of the world to declare now or at any other time the objects which it has in view.

We have entered this war because violations of law have occurred that have deeply affected us and made the lives of our people impossible unless they were corrected and the world was once and for all assured against their repetition. Therefore, what we are asking in this war is not something specific to us. It is that the world may be made fit and safe to live in, and especially that it may be made safe for every peace-loving nation which, like our own, desires to live its own life, to establish its own institutions, to be assured of justice and fair treatment from the other peoples of the world against selfish force and aggression. All the peoples of the world are, in fact, partners in this interest, and as far as we are concerned, we see very clearly that if justice is not done to others, it will not be done to us. Therefore, the program of world peace is our program; and that program, the only possible program, as we see it, is this:

I. Open peace agreements, openly arrived at, after which there will be no private international understandings of any kind, but diplomacy will always be conducted frankly and in public.

II. Absolute freedom of navigation on the seas, outside territorial waters, both in time of peace and in time of war, except when the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants.

III. The elimination, as far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of equal terms of trade among all nations consenting to peace and associating for the maintenance of peace.

IV. Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest level compatible with internal security.

V. A free, open, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based on strict adherence to the principle that in the determination of all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be settled.

VI. The evacuation of all Russian territory and the settlement of all questions concerning Russia so as to secure the best and freest cooperation of the other nations of the world in securing for Russia a free and unimpeded opportunity to determine independently her own national political and political development, and to secure for her a sincere welcome into the society of free nations under institutions of her own choosing; and, more than a welcome, assistance of every kind she may need and desire. The treatment accorded to Russia by the sister nations in the months to come will be the decisive test of their good will, of their understanding of her needs in relation to their own interests, and of their intelligent and unselfish sympathy.

VII. Belgium, the whole world will agree, must be evacuated and restored, without any attempt to limit the sovereignty which she enjoys in common with all other free nations. No other act will serve like this to restore the confidence of nations in the laws which they themselves have established and determined for the government of their mutual relations. Without this healing act the whole structure and validity of international law is forever impaired.

VIII. All French territories should be liberated and the portions invaded should be restored, and the wrong done to France by Prussia in 1871 in the Alsace-Lorraine question, which disturbed the peace of the world for nearly fifty years, should be repaired, so that peace may again be secured in the interests of all.

IX. A readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognized lines of nationality.

X. The peoples of Austro-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see protected and secured, should be given the freest opportunity for autonomous development.

XI. Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro should be evacuated; the occupied territories should be restored; Serbia should be given free and safe access to the sea; the relations between the several Balkan states should be determined by a friendly council, along historically established lines of loyalty and nationality; and international guarantees of the political and economic independence and territorial integrity of the several Balkan states should be concluded.

XII. The Turkish part of the present Ottoman Empire should enjoy secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities at present under Turkish rule should be assured of undoubted security of life and an absolutely unimpeded possibility of autonomous development, and the Dardanelles should be permanently opened as a free passage for the ships and commerce of all nations, under international guarantees.

XIII. An independent Polish state should be created, including the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, to which free and secure access to the sea should be ensured, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international conventions.

XIV. A general association of nations should be formed on the basis of specific conventions, with the purpose of providing reciprocal guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to large and small states alike.

In these essential rectifications of wrongs and assertions of rights, we feel ourselves close partners of all associated governments and peoples against the imperialists. We cannot be separated in interests or divided in aims. We stand together to the end.

We are willing to fight and to continue to fight for such agreements and understandings until they are achieved; but only because we want right to prevail and we want a just and stable peace, such as can only be secured by the elimination of the main provocations to war, which this program eliminates. We are not jealous of Germany’s greatness, and there is nothing in this program that affects it. We bear her no grudge for any achievements or distinctions in learning or peaceful enterprise, such as have made her record very brilliant and very enviable. We do not wish to injure her or in any way block her legitimate influence or power. We do not wish to fight her either with arms or with hostile trade agreements, if she is willing to associate with us and the other peace-loving nations of the world in agreements of justice, law and fair treatment. We only wish her to accept a place of equality among the peoples of the world – the new world in which we now live – instead of a place of domination.

A tragedy in one’s private life – whether it’s a family feud or an accident – is difficult for all people to cope with. We are the same with national tragedies. On the one hand, it is difficult to come to terms with a new, less favourable situation than before, and on the other hand, it is not easy to avoid the traps of blame-shifting explanations. One of the greatest such traumas in the history of the Hungarian nation is the Trianon Peace Treaty of 1920. Not primarily because it meant that Hungary lost around two-thirds of its territory and national wealth. It was also because more than three million Hungarians lived in the annexed territories. Moreover, about one third of them were located directly on the other side of the new borders, i.e. within arm’s reach of the Hungarians of the new Hungary. This made it difficult, and often impossible, even for those who had otherwise accepted the right of the nationalities of a multi-ethnic Hungary to establish their own state.

The unexpected and enormous shock led to decades of fabulous and blame-shifting explanations. Some of them are still alive today. Over the decades, however, Hungarian historiography has developed a rational explanatory scheme that has credibility not only in Budapest but also around the world. The break-up of the Habsburg Empire and, within it, of historic Hungary, was caused by a confluence of factors. First and foremost was the multi-ethnic nature of the empire and Hungary, and the discontent of the national elites.

The second important reason was the irredentist policy of the new states that emerged along the southern and eastern borders of the empire – Italy, Serbia and Romania. In other words, the fact that all three of them sought to seize the monarchical territories in which the sons of their own nation – or their own nation – lived. The interests and strategic considerations of the victorious great powers also played a decisive role. And finally, we cannot leave unmentioned the chaotic Hungarian conditions in the months following the war, which for a long time made it impossible for a Hungarian peace delegation to travel to Paris, the venue of the peace conference.

1. The nationality question

Before the outbreak of the First World War, the Austro-Hungarian Empire covered an area of 676,600 square kilometres and had a population of 51.3 million. This population of over half a hundred million was divided into seven major religious groups and 12 major linguistic-ethnic groups. None of the linguistic-ethnic groups constituted an absolute majority. The largest group, almost 12 million, were Germans, but they accounted for no more than 24%. Hungarians followed the Germans in both population and proportion (10 million, or 20 per cent). Czechs had 13 percent, Poles 10, Ukrainians 8, Romanians 6.5, Croats 5, Serbs and Slovaks 4-4, Slovenes 2.5, Italians 1.5 percent. Under the Austro-Hungarian reconciliation of 1867, the Habsburg Empire consisted of two states: the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. Starting from Bukovina and extending through Galicia, Bohemia and the Austrian provinces to Dalmatia, the Austrian territories embraced the Kingdom of Hungary in a crescent shape, which was divided into two parts in terms of constitutional law: Hungary proper (in the narrower sense) and Croatia. In the Austrian Empire, 35.6 percent of the population was German-speaking, while 48 percent of the population of the Kingdom of Hungary was Hungarian-speaking. The main victims of the dualist system were the Czechs, who wanted to federalise the empire. However, the two most powerful nations in the empire, the Germans and the Hungarians, were alarmed by this prospect. As a result of this double opposition, the ‘Czech reconciliation’ was taken off the agenda. As a result, the Czechs became the most determined opponents of the dualist system. By the turn of the century, a markedly pro-Russian trend had emerged among the younger Czech generations. Alongside the overtly or covertly separatist tendencies, the old Austro-Slavic federalist ideas continued to survive at the beginning of the 20th century. One of these was developed by a then unknown young teacher, Eduard Beneš, in 1908. Combining the nationality and the history principle, Beneš envisaged seven or eight federal units. The Czech-Moravian territories would form a single state together with Slovakia, and the southern Slavs would be part of one or possibly two political entities.

As a result of their extensive self-government rights and influence from Vienna, relations between Polish elite groups and the imperial leadership remained cordial and harmonious throughout the dualist period. Nevertheless, national unity and independence remained a strategic goal for the Poles in Galicia. The Ukrainians were the most underprivileged people in the empire, and perhaps for that reason among the most loyal subjects of the Habsburgs. Nevertheless, in contrast to the old conservative political masses led by the clergy, in the 1880s and 1890s there was a trend among them to unite the Ukrainians of Galicia and Russia rather than maintain the status quo, and there were also pro-Russian currents that looked to the tsar for help.

The most loyal southern Slavs in the empire were Slovenes without a state tradition. Although anti-Hapsburg sentiment had also emerged among them immediately before the war, the vast majority of them hoped for a trialist solution that would have brought the southern Slavs of the empire into line with the Germans and Hungarians.

Despite Croatia’s high degree of autonomy, Croatian-Austrian and Croatian-Hungarian relations remained tense. Alongside the ‘Magyaron’ parties that accepted and respected the 1868 settlement, by the turn of the century movements had emerged that sought to break the Hungarian-Croatian state-community ties and to give the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, united with Dalmatia and Rijeka, the status of equal to that of Hungary. The third major trend within Croatian political ideas is the redefinition of the Irish idea. It aimed at the unification of all South Slavic peoples, except the Bulgarians, outside the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

From the turn of the century onwards, the federative aspirations of the peoples of the Monarchy, which continued to live and grow, became a matter of increasing concern for the imperial leadership and the German parties of the Austrian state. It was becoming increasingly clear that the dualist construct was not suitable for the effective long-term operation of a multi-religious and multi-ethnic state in an age of modern nationalisms. From the top, the heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand, was above all planning a far-reaching structural reform of the empire. The members of his workshop, the Belvedere Circle, sought to federalise the Monarchy along national lines.

Unlike the Austrian Empire, which had traditionally provided scope for provincial particularism, the Kingdom of Hungary had been a unitary state until the 16th century, and the Hungarian elite continued to insist on this after its restoration in 1867. Consequently, while the Nationality Act of 1868 granted equal rights to all citizens of the country, regardless of race, language or religion, and even provided for many elements of cultural autonomy for nationalities in the ecclesiastical and educational spheres, it did not recognise them as political nations, i.e. as equal partners in the creation of the state. The Hungarian government rigidly refused to grant the territorial autonomy demanded by the nationalities as early as 1848-49, and not only in the legislature and government, but also in time made Hungarian the almost exclusive language of the administration.

As tensions between privileged communities, recognised as nations, and peoples treated as nationalities escalated, so did the antagonism between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Austrian Empire at the beginning of the 20th century. Behind these conflicts lay a conflict of interest between the pro-reconciliation groups of the Hungarian ruling classes and those groups critical of the common institutions of the dualist system. By 1904, this conflict of interests had led to the complete paralysis of Hungarian parliamentary life and the emergence of an anti-dynastic and anti-imperialist mood unprecedented since the period of neo-absolutism after 1849.

2. The war aims of the First World War

The First World War was fought over territory. During the war, each of the warring parties outlined their objectives. Serbia, whose conflict with the Monarchy ultimately sparked the war, informed its allies as early as 4 September 1914 that in the event of victory it intended to “create from Serbia a strong southern Slav state whose population would be composed of all Serbs, all Croats and Slovenes”.

Among the neighbouring states of the Monarchy, Italy and Romania also made far-reaching territorial claims. For the southern provinces of the Monarchy, which were partly inhabited by Italians, Rome had formed an unconditional claim. In the secret treaty concluded in London on 26 April 1915, in which Italy, in opposition to its former allies, promised to go to war on the side of the Entente, Italy obtained guarantees from its new partners, particularly for its claims to the Adriatic. These areas were South Tyrol and Valona (Albania), Istria and the islands of the Kvarner Bay, Trieste and its surroundings, and North Dalmatia as far as Spalato. Of the territorial claims, some of which were based on linguistic-ethnic, others on strategic grounds, the only one rejected by the Allies was the cession of South Dalmatia, because this part of the coast was destined for Serbia. After long negotiations, Romania finally sided with the Entente in August 1916. In exchange for his entry into the war, he was promised all of Transylvania, Maramures, Partium, the eastern edge of the Tiszántúl roughly up to the Debrecen-Szeged line, Banat, and Bukovina up to the Prut River. On 27 August 1916 the Romanian army invaded Transylvania, confident of an Entente victory and hoping to gain the above territories.

Alongside the irredentist nation states along the borders of the Monarchy, the non-native nationalities of the empire naturally outlined their vision of the future. The Poles, regardless of which empire they fought under, aimed to reunite their nation and gain independence. The Polish leaders who sided with the monarchy, and thus the central powers, saw this as being achieved through Austro-Hungarian or German puppetage, while those in Russia, and thus in the Russian army, saw it as being achieved by winning the goodwill of the Tsar. In their declaration of 29 May 1917, the Czech leaders stressed ‘the need to transform the Habsburg Monarchy into a federation of free and equal national states’. One such unity would have resulted from ‘the unification of all branches of the Czechoslovak nation’, including of course the Slovaks. Other Czech politicians, however, had essentially taken a separatist position since the beginning of the war. Alongside Karel Kramar and Václav Klofáć, who envisioned the creation of a Czechoslovak state within the framework of a large Slavic confederation led from St Petersburg, Eduard Beneš and Tomaš G. Masaryk, a professor at the University of Prague, were also part of this group, but after leaving for foreign countries they were oriented more towards the Western antipowers.

Like the Czechs, the South Slav representatives in the Vienna Imperial Assembly did not advocate full independence, but federalisation and the creation of a South Slavic entity within the federation. In their declaration of 30 May 1917, they accordingly set themselves the goal of ‘the unification of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs living in all the provinces of the Monarchy’ and the autonomy of the territories they inhabited within the Monarchy. The South Slavic Croatian emigration, mainly in Dalmatia, on the other hand, stood on the platform of secession from the Monarchy and unification with Serbia.

In May 1917, the Ukrainian representatives also declared their desire to create a federal unit within the Habsburg Empire from the Ukrainian-inhabited parts of the Monarchy and the Ukrainian-majority western provinces of the Russian Empire, as the Czechs and the South Slavs had demanded for themselves. In contrast to the Polish, Czech and South Slavic movements, the Slovak and Romanian organisations in Hungary showed little activity until the last phase of the war. When they did make themselves heard, they usually made declarations of loyalty to the Monarchy and Hungary.

The territorial claims against the Habsburg Empire and the disintegration of the empire were supported above all by Russia, which was one of the enemy powers. Russian war aims revived Russian expansionist plans with a long history and a pan-Slavic motive.

The war aims of the Western antagonist powers, on the other hand, did not initially include the creation of new and independent nation states in East-Central Europe. Despite its growing internal weakness, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was still seen by many as a balancing factor in the European system of states, and it was therefore considered expedient to maintain it. Initially, the programme of converting the Danube Empire into a nation-state was represented only by the old intellectual critics of the dualist system, Seton-Watson and Wickham Steed in London and Louis Leger and Ernest Denis in Paris. However, their influence was limited. This explains why, during the first two years of the war, Britain and France did not support either Polish or Czech separatism, and made concessions to the national principle only where and to the extent that they offered tangible advantages in terms of changing the balance of power in the war.

This indifference to the aspirations of the nation-state gradually diminished from 1916, giving way in 1918 to a militant commitment to the principle of national self-determination. What was the reason for this change? The first important impetus came from the fear of the German Mitteleuropa plans that had been in the air since 1915, namely the outline of a German-Austrian-Hungarian controlled ‘Greater Area’ stretching from the Rhine to the Dnieper and the Black Sea. The South Slavic, Czech and Polish politicians in exile, as well as their British and French supporters, saw this as evidence of the emergence of continental German hegemony. The second Russian Revolution and the signing of the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty in March 1918 contributed to this. With this peace, the Western allies lost their most important partner in the East, and the contours of an informal German empire up to the Dnieper were in reality outlined. The scandalous breakdown of the special peace negotiations with Charles IV in April 1918 also had a negative impact. This left Charles in a humiliating and vulnerable position vis-à-vis Berlin. This was reflected in the Treaty of Spa, which provided for close economic, political and military cooperation between the Monarchy and Germany, signed on 15 May 1918. The latter two events were interpreted in London, Paris and Washington as meaning that the Monarchy was now definitively on Germany’s treadmill and would in no way be able to play the balancing role that many had believed it was capable of in 1916-1917. From the spring of 1918 onwards, therefore, the politicians of the Entente powers were no longer debating whether or not the Monarchy should be preserved, but where the borders of the new states that would replace it should be drawn.

3. The revolutions of 1918-1919 and the break-up of historic Hungary

On 23 October, the Wekerle government resigned, realising the consequences of its defeat in the war and its own powerlessness. The next day, a successful Italian offensive began near the Piave, which led to the revolt of some joint regiments. It was in this situation that the radical opposition parties decided to set up an alternative deliberative and governing body of the nation, the Hungarian National Council. It was formed on the night of 23 to 24 October 1918 under the leadership of Mihály Károlyi. Its 12-point manifesto demanded an immediate end to the war, the establishment of the country’s independence, the introduction of far-reaching democratic reforms and reconciliation with the nationalities without prejudice to the country’s territorial integrity. The Károlyi government formed on 31 October had the same programme.

The government’s first major step was the conclusion of a military convention with the commander of the French forces in the Balkans, General Franchet d’Esperey, on 13 November. The 18-point treaty stipulated that the Hungarian government was obliged to evacuate the Transylvanian and Banatian territories east of the upper course of the Szamos, south of the Mures line and south of the Szeged-Baja-Pécs-Varasd line. The Károlyi government saw this as a temporary solution and hoped that the peace treaty, which would be the final settlement, would not only guarantee the country’s sovereignty but also seek to be fair in the border issue.

In the days following the signing of the treaty, the Serb-French and Romanian forces quickly took possession of the territories east and south of the demarcation line, and at the same time the first Czech legions appeared in the Slovak-populated western zone of Upper Hungary. The chances of reaching an agreement with the representatives of the national minority population, which the government considered to be a fundamental task, were considerably reduced by this circumstance. Oszkár Jászi’s proposals for the cantonisation of Transylvania in Arad on 13-14 November were rejected by the Romanian National Council. At their meeting in Gyulafehérvár on 1 December, the Romanians declared their union with the kingdom. The following day, the Romanian army crossed the demarcation line in Belgrade and began annexing the territories promised to it in the 1916 Treaty of Bucharest. By Christmas they had reached Cluj-Napoca.

Negotiations with the Slovaks got off to a more confident start. One of their leaders, Milan Hodza, agreed during talks in Budapest at the end of November a demarcation line with Jasi and the Minister of War, Albert Bartha, which roughly corresponded to the Slovak-Hungarian linguistic dividing line. But for other Slovak leaders, and especially for Prague, such a solution was unacceptable. Hodza was therefore disavowed and, using their contacts in Paris, the Entente powers used their list of 23 December to establish a demarcation line much further south, essentially coinciding with the political border that was later agreed. No negotiations were held with the Serbs, who simply declared the accession of the occupied southern Hungarian counties to Serbia at their assembly in Novi Sad on 25 November. Loyalty to Hungary was shown only by a section of the scattered Germans and by a section of the Rusyns, the most underdeveloped ethnic group.

The de facto loss of Transylvania, the Felvidék and the South was a source of deep consternation for the government and the public alike. At the same time, no comprehensive measures were taken to stop the enemy advancing and partly crossing the demarcation lines. Károlyi and his entourage believed that an organised military resistance would damage Hungary’s chances at the peace conference. The partly spontaneous resistance in the Highlands and the Székely detachment in Transylvania, which was in permanent retreat and occasionally engaged the Romanians in battle, therefore received only limited support. Thus, ever larger areas came under foreign rule.

It was only at the beginning of 1919 that Károlyi decided to take organised action against the Czech legions and the Romanian army. The final impetus for the change in his pacifist policy, based on the goodwill of the victors, came from the decision of the Paris Peace Conference on 26 February, which he received on 20 March from the French Lieutenant-Colonel Vix, who represented the Allies in Budapest. This included the possibility for Romanian troops to advance as far as the Satu Mare-Nagykároly-Nagyvárad-Arad line, and to the west of this a neutral zone would be established, which would include Debrecen, Békéscsaba, Hódmezővásárhely and Szeged. Károlyi rejected the note on 21 May, and planned to rely on Soviet Russia to announce national resistance and to appoint a government of social-democratic politicians to support the foreign policy turnaround at home, while retaining his position as head of state. But his calculation was flawed. The majority of the Social Democrats did not want to form a government on their own, and so on the afternoon of 21 January, behind Károlyi’s back, they agreed with the Communist leaders in the Collector’s Prison to take power together. By the morning of 22 March, red flags were waving in the wind on the houses of Budapest, and bold posters announced that the “proletariat” had taken power in Hungary. The victory of the proletarian dictatorship in Hungary surprised and even frightened the surrounding states and the peace conference in Paris. It was feared that the revolution would not stop in Hungary, but would spread westwards, as the Bolsheviks had hoped and assumed, and that Soviet regimes would be established there too. They therefore agreed to a military attack on the Soviet Republic.

Because of the failure to organise the army, the Soviet Republic inherited an army of barely 40,000 men from the bourgeois democratic system. As a result of recruitment, which began on 30 March, by mid-April this number had increased by about 20 thousand. However, the Romanian army still had a superiority of several times its strength, and in fighting that lasted barely two weeks, it had occupied the entire Transdanubian region by 1 May. Taking advantage of the weakness and exhaustion of the Hungarian forces, Czech troops crossed the demarcation line on 26 April and in a few days occupied Munkács, Sátoraljaújhely and a large part of the industrial region of Miskolc. In the same days, French and Serbian forces took Mako and Hódmezővásárhely.

In order to avoid an imminent end, the Revolutionary Governing Council called the workers of Budapest and the countryside to arms on 20 April and organised recruiting rallies throughout the country. The Red Army thus doubled its numbers in a week or two, reaching 200,000 by the end of May. The majority of the applicants were refugees from Trans-Transdanubia, poor peasants from the Stormy Region, the unemployed, enthusiastic young people, and workers from Budapest who were organised into separate battalions. There were also a good number of professional officers and non-commissioned officers, as well as national and local leaders of the revolution. ‘In not letting our ancestral land go, the communist meets the nationalist’, a rural journalist explained this somewhat strange situation.

After sporadic clashes, the reorganised Red Army launched its general counter-offensive on the northern front on 20 May. Thanks to the enthusiasm of the soldiers and professional management, the northern campaign was a surprising success. In less than three weeks, the attacking wedges reached as far west as the Garam valley and as far north as the Banská Bystrica-Rosnoye-Bartfa line. With Hungarian support, the Slovak Soviet Republic was proclaimed in Eperje on 16 June 1919.

On 13 June, the Peace Conference responded to the Hungarian military successes by announcing the final borders of Hungary in relation to Romania and Czechoslovakia. At the same time, it demanded the evacuation of the recaptured northern territories in return for a promise to surrender the Tisza Transdanubia. The revolutionary general staff debated the response to the ultimatum for several days. The majority, including a good part of the communists and the military leaders, opposed the withdrawal. However, Béla Kun, citing the increasingly counter-revolutionary mood in the hinterland, recommended acceptance of the diktat, and his position eventually prevailed.

After the retreat at the end of June, the Soviet Republic attempted to strengthen its weakened base. Kun and his associates therefore decided to attempt the liberation of the Tiszántúl. However, the offensive, which started on 20 July, collapsed within a few days. The Red Army withdrew and its forces began to disintegrate. On 30 July, the pursuing Romanian troops crossed the Tisza at Szolnok, opening the way to the capital.

Faced with a desperate situation, the Revolutionary Governing Council resigned on 1 August and handed power to a government of moderate social-democratic politicians. However, the Peidl government remained in office for only a week. After his resignation, a right-wing government led by István Friedrich took power, while the Romanian army controlled most of the country and the National Army led by Miklós Horthy took up positions in the southern part of the Transdanubian region. It was in these circumstances that the invitation letter from Paris finally arrived: Hungary was to send a delegation to the peace conference, which was drawing to a close.

4. Activities of the peace delegation and the adoption of the peace treaty

The Hungarian peace delegation, led by Count Albert Apponyi, arrived in the French capital on 6 January 1920. The draft Hungarian peace treaty, which was supposed to have been negotiated, had been ready for several months. The future borders of Hungary were agreed by the territorial subcommittees of the Conference in February-March 1919. The supreme bodies of the Conference approved these proposals in May-June 1919, after minor debates, but without any substantive changes. The only exception was the Austro-Hungarian border. This was only decided on 10-11 July 1919. The new borders were the result of a compromise between the more equitable ideas of the victorious powers and the exaggerated demands of the allied or allied successor states. As a result, the principle of nationality, proclaimed as a fundamental principle, was in many cases subordinated to strategic, economic and other considerations.

The Hungarian delegation received the draft peace treaty on 15 January 1920. The territory of the new Hungary was 93,000 square kilometres, compared with 282,000 square kilometres before 1918 (excluding Croatia), and its population was 7.6 million, compared with 18.2 million before. The victors stipulated that Hungary could only maintain an army of 35,000 volunteers, or mercenaries. General conscription was forbidden. Hungary could neither manufacture nor purchase armoured vehicles, tanks, warships and combat aircraft, which were essential for modern warfare. The Danube flotilla had to be handed over to the Allies. Further paragraphs stipulated that from 1921 onwards, Hungary would be obliged to pay reparations for war damages caused by it for a period of thirty years.

On the same day, 15 January 1920, the Peace Conference Secretariat received the so-called preliminary lists of Hungarian positions. There were twenty documents in all, accompanied by numerous statistical, map and other annexes. They contained detailed data on Hungary’s geographical, economic and cultural conditions, as well as on the linguistic distribution of its population and its educational level. In general, the Hungarian lists argued for the preservation of the unity of historical Hungary. In only one case, however, was the possibility of a compromise on the question of Transylvania’s internal organisation and its internal structure raised. The essence of what was said in List VIII on the Transylvanian question was to organise the internal relations of Transylvania on the Swiss model, to reconsider the territorial affiliation of the territory and to ask the opinion of the local population.

On 16 January 1920, after receiving the draft peace treaty and the preliminary Hungarian lists, Albert Apponyi was given the opportunity to express the Hungarian position orally before the representatives of the five main powers – France, Great Britain, Italy, the USA and Japan. During the meeting, which lasted about an hour and a half, Apponyi presented the Hungarian position in French and English, and then briefly summarised it in Italian. The essence of what he said was the same as in the preliminary notes: to maintain the unity of historic Hungary. To this end, he put forward historical, economic, geographical, cultural and even linguistic-ethnic arguments. At the same time, it also stated that if these arguments were rejected, i.e. if the borders in the draft were to be maintained, Hungary would call for a referendum. After the speech, Lloyd George took the floor. The British Prime Minister asked how many Hungarians would live in neighbouring countries if the borders were to be implemented. In particular, he was interested in where the Hungarian ethnic group that was being cut off was located: along the border or far from the new country, forming language islands. Apponyi then sat down near Lloyd George and laid on his desk the now famous ethnographic map of Telekaura, on which the Hungarian population was marked in red. The map also showed the proposed new borders, having been carefully drawn by Teleki the previous evening. Thus it was clearly visible that not only remote linguistic islands would be under foreign rule, but also a very significant number of border Hungarians.

On 18 January Apponyi and the majority of the delegates travelled home to Budapest with the received plan, and on 21 January they informed Horthy and the government, and at the same time determined the order and theme of the reply notes. In the following days, the experts drew up 18 new documents. The idea of integrity was still the main theme of these new documents, but with a marked shift towards the ethnic principle and the referendum. The Peace Conference received the new Hungarian lists on 12 and 18 February 1920. Apponyi’s appearance on 16 January and the Hungarian lists were not without effect. Hungarian objections to the draft peace treaty in January and February were first discussed by the Supreme Council of the Peace Conference on 25 February 1920. On this occasion, both British Prime Minister Lloyd George and Italian Prime Minister Francesco Nitti recommended that the Hungarian comments be carefully considered. Millerand, the new French Prime Minister, on the other hand, considered any renegotiation of the question superfluous. His position was that all decisions taken so far on the Hungarian peace treaty should be considered valid without change.

At the meeting of the Supreme Council on 3 March, Lloyd George returned to the question of the Hungarian frontiers. Citing precise statistics, he pointed out that the peace treaty planned to place almost three million Hungarians, or ‘a third of the entire Hungarian population’, under foreign rule, and that this ‘will not be easy to defend’. There will be no peace in Central Europe, he predicted, “if it turns out afterwards that Hungary’s claims are justified and that whole Hungarian communities have been handed over to Czechoslovakia and Transylvania like herds of cattle simply because the conference refused to discuss the Hungarian cause”. In the debate, Nitti again sided with Lloyd George. However, Philippe Berthelot, the French Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, who represented France in Millerand’s absence, was adamantly opposed to the Anglo-Italian proposal. The compromise finally agreed was to postpone the decision and refer the whole matter to the Council of Foreign Ministers and Ambassadors.

The Council of Foreign Ministers and Ambassadors put the question of a possible change of the Hungarian borders on the agenda on 8 March. The long debate resulted in the original decisions being upheld. The only concession made at the suggestion of British Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon was that if the Boundary Commissions “as a result of a thorough on-the-spot examination, should find that in some places injustice has been done and that a change is necessary, they should have the right to report their views to the League of Nations”. Finally, it was also agreed that the possibility of subsequent modification would not be included in the text of the peace treaty, but would be brought to the attention of the Hungarians in a separate covering letter.

After receiving the final text of the peace treaty, the peace delegation resigned on 19 May 1920. Looking back on their activities, the delegates stressed that they had succeeded in making foreign public opinion realise that the decisions of the Peace Conference on Hungary and the clauses of the peace treaty were deeply unjust, and therefore “cannot be permanent and will only become a source of new complications and wars”. Nevertheless, their view was that the peace should be concluded because Hungary lacked the economic, diplomatic and military backing behind it that could be relied upon to refuse to sign. Armed resistance by Turkey, one of the losing states, would thus only lead to further suffering and sacrifice in the Hungarian context, without the slightest hope of success. It was exactly 90 years ago, on 4 June 1920, that the document was signed in the palace of Trianon the Great in the gardens of Versailles.

(First published in Népszabadság, 5 June 2010)

In his book Ignác Romsics has taken on the task of addressing a sad and tragic series of events in the history of Hungary in the 20th century, the process of the loss of Transylvania, Banat and Partium and their passage under foreign rule. The process by which 103,000 square kilometers with 5.2 million inhabitants came under the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Romania. The work is divided into three chapters and a

a preface and an afterword. The first chapter presents the historical background: a brief history of Transylvania, the peoples who inhabit it, the history of their numerical development, the national sentiment that arose and grew within them. The first chapter describes the situation in Transylvania up to the last year of the First World War, and in this chapter we also learn about the plans of the Kingdom of Romania for Transylvania, which it tried to implement with the help of the Entente. The second chapter of the book – which, with its more than 200 pages, is in fact the backbone of the book, in a way a book in itself – deals with the process of imperial change. It provides a vivid and evocative description of the sequence of events during which Transylvania gradually came under the control of the Kingdom of Romania. A description of how the Hungarians, Germans and Romanians living there experienced in the course of their daily lives the change during which Hungarian sovereignty disappeared, the power of the Hungarian state disappeared and was replaced – in some cases almost surreptitiously – by the power of the Romanian state. How, step by step, the feeling that this was only temporary, that it could not last, gradually disappeared from the Hungarians; how this feeling was gradually replaced by a feeling of discouragement, resignation, resignation. In this chapter, the author also illustrates how Transylvanian Hungarians thought about the strategy they should choose in order to survive after the establishment of Romanian rule. Yes, I think it is not wrong to use this term: survival. No one knew at the time how long it would last

but everyone expected Hungary not to abandon the Hungarians of Transylvania – and indeed, on June 4, 1920, the whole of Hungary was in mourning. After 1920, the idea of territorial autonomy for Transylvania (Szeklerland) was not yet a central issue. In the long term, Transylvanian Hungarians did not hope for autonomy, but for revision, for a return to Hungary, and tried to develop their survival strategies on this basis. The Hungarian political leadership also represented the idea of an integral Hungary and, in fact, this is even evident from Count Albert Apponyi’s speech at the Paris Peace Conference. This is the only part in which the author criticizes the Hungarian political leadership for some shortcomings, carelessness and prudence: perhaps if the peace conference had emphasized the ethnic principle, if Hungarian cultural supremacy and historical rights had not been so strongly emphasized, things might have turned out differently. Incidentally, the author does not polemicize on this issue: although he rightly criticizes and criticizes the practice of Hungarian nationality politics in the era of dualism, the book does not seem to castigate Hungarian politics, responsibility, mistakes or even crimes of Hungarian politicians. What struck me most while reading the book is that Ignác Romsics masterfully makes it clear that the fate of Transylvania was not decided in Transylvania, not by Transylvanians, not even in Bucharest or Budapest – not in 1918-1920, not in 1944-947. After both world wars, Transylvania’s fate was decided far from Transylvania, but far from Romania and far from Hungary – in Paris, Vienna and Moscow. Not once have the Transylvanian people been asked what they want – and this is all the more tragic and depressing in the light of the beautiful idea and principle that American President Woodrow Wilson put forward and which Transylvanian Hungarians and Hungarian politicians hoped in vain to apply at the Paris Peace Conference in 1920. Transylvania was the instrument and object of Great Power games in 1920 and remained so in 1947. In this context, Hungarian nationality policy could have been practically as humane as possible, but this was not the objective. The third chapter deals with the period between the two world wars, the situation after the second Vienna decision and the fate of Transylvania after 1944. The road leading to the Paris Peace Treaty of 1947 is also described here. After World War II, the Hungarian political leadership took a very different approach to Transylvania’s future.

The Hungarian leaders tried to influence and shape the fate of Transylvania in a more realistic way, taking into account the situation and the interests of the great powers: more realistic, but still not realistic enough. Instead of asserting Hungary’s historical rights and integrity, they only tried to convince the Great Powers to return to Hungary first a 22 000 square kilometer strip along the Hungarian-Romanian border, and later a strip of barely 4 000 square kilometers. But Great Power interests did not grant even this small wish. And yet there is no question that the Great Power leaders who drew the borders and decided the fate of the nations are evil, blinded by hatred of Hungarians and fools. It is as if they themselves had become prisoners of their earlier promises, of their desires and dreams of their imagined influence over Central Europe, of their domination, to which they subordinated the fate of several million people – and about which, of course, nothing was realized afterwards. Just as the Hungarians in Transylvania remained prisoners of their wishes and dreams in 1946-1947, at the time of the Peace Treaty of Paris – even though the idea of autonomy, which had been thoroughly elaborated, had by then taken on a much more important role. Perhaps it will be useful one day. Let’s hope so.

Szilárd Szabó

lawyer, political scientist,

assistant professor,

University of Debrecen